William Shakespeare asked that question in Romeo & Juliet. “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Juliet was not allowed to associate with Romeo because he was a Montague. If he had any other name, it would have been fine. She was complaining that his name is meaningless. If the rose had any other name, it would still be the same. So, with Romeo- he would still be the same beautiful young man even if he had a different name.1

Our name is how we are identified from birth. It represents us conceptually to others. Hearing someone’s name that we know often brings their face, personality, or character to mind. We can remember conversations, funny anecdotes, or life encounters that inform our opinion of who they are. When we hear a stranger’s name it is just a name until we have information to associate with it. Information may come in the form of gossip passed along from another person, social media viewed online, or news reports.

Back in the day before the internet, employers would review applications and resumes to screen for potential job candidates. Calls or letters would be sent to verify employment history. References would be contacted to gain information necessary to inform the hiring process. Businesses routinely run background checks on job candidates and active employees to determine if they should be disqualified from employment opportunities. Once I was fingerprinted because the FBI had to check to ensure that I did not have any mafia connections when I applied to work as the lab manager at a landfill.

Modern hiring practices have changed significantly because of the potential of litigation regarding the release of information that could be considered negative regarding a former employee. Your previous employer will now only confirm that an individual worked for the company. To get information, many employers have turned to third party companies that collect massive amounts of information about individuals from a wide variety of companies and government agencies that have commoditized their vast databases. Information about credit worthiness, social media posts, along with court filings and criminal convictions are available instantaneously.

I was recently fired from a job after 6½ years because of a change in hiring policy. When I was first hired the policy was that you could not have a criminal conviction in the last 7 years. A new change to the policy specified that you could not have certain specific convictions period. My employer knew who I was based on years of interaction- a hardworking, intelligent, dedicated, and loyal employee. Yet based on a single entry in a background check I was dismissed without any opportunity to explain.

The issue with computer data has always been “Garbage In, Garbage Out”. The information is only as good as the source. While it may be useful in this age of information overload to get information in small, overly simplified bites, context is everything, as it is in life. When we spend our lives with a person, we will have a much better image of who they are than if we only read the sensationalized headlines about what might be the worst day in someone’s life. And yet it is those snapshots, those life events presented without context by which our society makes life altering decisions about other people.

Case in point is SORNA, the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act. In 1994 the Wetterling Act established baseline standards for states to register sex offenders. Megan’s Law in 1996 mandated public disclosure of information about registered sex offenders and required states to maintain a website containing registry information. The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act, which includes SORNA, created a new baseline of sex offender registration and notification standards.2 The registering and tracking sex offenders went from being a tool useful to law enforcement to a modern-day Scarlet Letter. It is the public shaming, disenfranchising and discrimination of people who, in addition to many serving long jail/prison sentences, now face additional civil penalties including restrictions on where they can live and who they can live with.

In July of 2025 President Trump signed an executive order entitled “Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets”.3 In Section 3 the order zeroes in on registrants who are homeless, instructing the Department of Justice to “substantially implement and comply with” the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA) for individuals with no fixed address. It calls for mapping and monitoring the locations of homeless sex offenders, effectively treating poverty as a risk factor warranting heightened surveillance.

The order goes even further. If a homeless individual is arrested for a federal crime, they may be evaluated under 18 U.S.C. § 4248, a statute that allows for indefinite civil commitment of individuals deemed “sexually dangerous”—even after they’ve completed their sentence. That’s not rehabilitation. That’s preemptive detention.

This isn’t about protecting the public or preventing new offenses. It’s about maintaining a narrative that portrays registrants as permanent threats, regardless of evidence. And it comes at the expense of people who are already marginalized—those struggling with mental illness, addiction, or simply trying to survive without stable housing in a system designed to push them out.

Supporters of the executive order may argue it’s a step toward restoring order. However, safety rooted in fear and endless punishment is not justice; it’s containment. What this order reveals isn’t reform, but the further cementing of a system that punishes for life, with no offramp, no redemption, and no demonstrated public benefit.4

In the Old Testament King Solomon wrote in Proverbs 22:1 “A good name is more desirable than great riches; to be esteemed is better than silver or gold.” This verse emphasizes the importance of a good reputation and the value of being respected over material wealth. It suggests that a good name reflects one’s character and integrity, which are more enduring and impactful than material possessions.5 This is a lesson that anyone who has been to prison learns the hard way. Not everyone that gets convicted is a “hardened” criminal. And once your good name is gone, it is impossible to get it back.

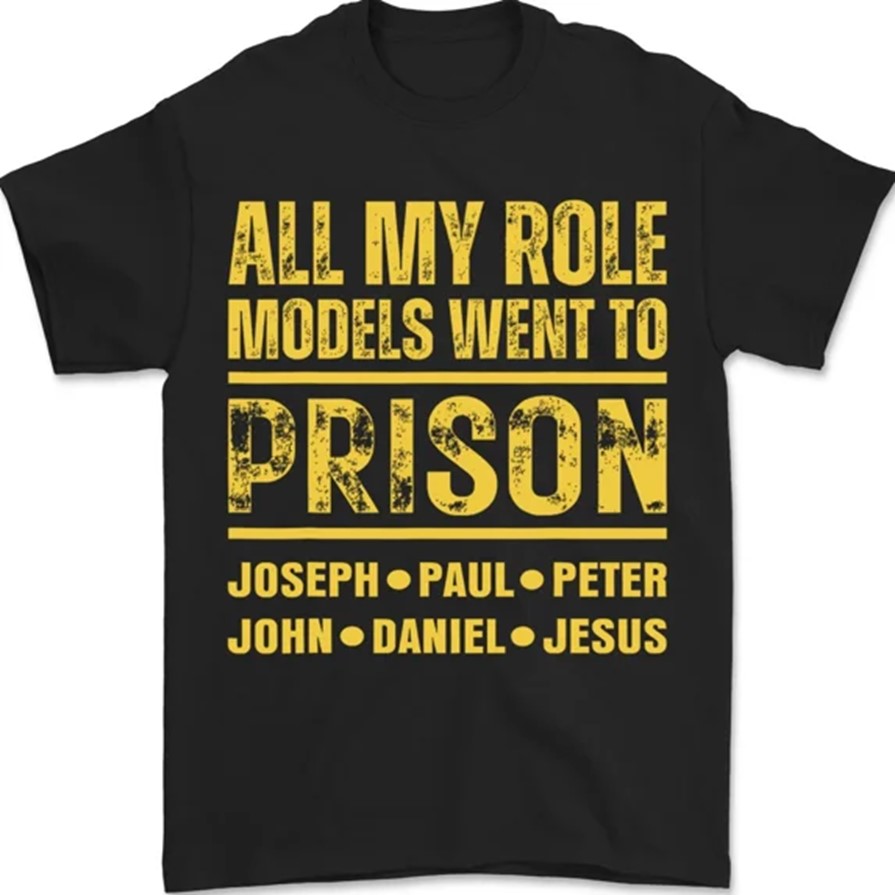

Many people that I met in prison were there because of one bad choice that was not in line with who they are, how they were living or their belief system. The downfall of Adam and Eve in Genesis chapter 3 was that they believed the lies of the Satan and ate of the forbidden fruit. Romans 3:23 says that “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” Yet the Bible is a narrative on redemption. In both the Old and New Testaments God used people that went to prison to do great things. I have a tee shirt that says, “All my role models went to prison: Joseph, Paul, Peter, John, Daniel and Jesus.” God used ordinary people, fallen people, people who sinned. He redeemed them, he changed them, and he used them for His glory.

In our society we have lost this prospective. Forgiveness has been replaced by Condemnation. Restoration has been replaced by Punishment. Redemption has been replaced by Damnation. There were two other people crucified on Golgotha with Jesus. Their choices are the same ones that we must all make. Either we choose to believe or we choose to reject the promise of eternal life. Yet it is the crowd surrounding the condemned that were jeering, hostile and calloused to the barbarous, gruesome execution taking place. These people are the true face of evil.

“There but for the grace of God go I” is an old proverbial phrase used to express empathetic compassion and a sense of good fortune realized by avoiding hardship. An early version was ascribed to the preacher John Bradford who died in 1555. 6 The Keryx volunteers that go into prisons say the same thing. There isn’t much that separates them from those in prison, just that they did not get caught. What our society needs today is more John Bradford’s and more Keryx volunteers. Men and Women of faith that acknowledge the saving grace of Jesus, not just in their own lives but in the lives of others. People that get involved, get to know people for who they are, not a stereotype or a caricature.

End Notes

1 ‘What’s In A Name’: Phrase Meaning & History✔️

3 Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets – The White House

4 Trump’s Executive Order Confirms the Registry Machine Isn’t Going Anywhere – Women Against Registry

5 What does Proverbs 22:1 mean? | BibleRef.com

6 Quote Origin: There But For the Grace of God, Go I – Quote Investigator®