There has been much said about whether or not those convicted of committing a crime should be given a second chance. A wide variety of voices in our culture have made their opinions perfectly clear. “Tough On Crime” was a political approach that emphasizes strict enforcement of laws and harsher penalties for offenders, often associated with policies aimed at reducing crime rates through increased policing and incarceration. This strategy has been a significant part of political discourse, particularly in the United States, and has seen a resurgence in recent years among various political leaders. But does it really work?

The Southern Poverty Law Center reports that Mandatory minimums effectively shift the power of sentencing from judges to prosecutors, resulting in less objective and more politicized outcomes. Although they are largely used for drug and other nonviolent crimes, mandatory minimum sentences can apply to a wide range of offenses. When mandatory minimums are in effect, the ultimate sentence will be based on the specific offense charged. This means that prosecutors have enormous, unchecked power because by choosing which charges to bring, they are also selecting the sentence the person will receive if convicted. This results in an imbalance of power and a high risk of unfair outcomes. For example, regardless of guilt, the threat of specific charges that carry stiff mandatory minimums may encourage people to plead guilty to a different crime with lower penalties. Furthermore, the exploitation of mandatory minimums effectively prevents judges from considering the totality of the circumstances when determining an appropriate sentence after a person has been found guilty of a crime. Historically, one of the roles of judges was to adjudicate an appropriate punishment. Usurping the judges’ role is especially problematic considering 98% of federal convictions are the result of guilty pleas over which prosecutors completely control the terms; very few people resolve their case with a trial.

A primary rationale behind mandatory minimum sentences was to deter crime. Today, the average federal sentence for people convicted of a mandatory minimum offense is 151 months; when the mandatory minimum is for drug offenses, it is 138 months. Contrary to the notion that these sentences will have a deterrent effect, ample research demonstrates that mandatory minimums do not decrease crime and, in fact, they likely generate more crime. Ample research concludes that imprisoning people not only does not lessen the likelihood that people will reoffend, but it can actually increase it. This may be for a multitude of reasons: Prisons are a place of trauma, people released from prison face stigma and economic hurdles, and people may struggle to return to families and communities after being away for so long. A policy of seeking harsh sentences will not improve public safety, but it will certainly destroy communities.1

There’s a growing movement to replace the tough on crime approach with a more evidence-based, data-driven, and compassionate approach to criminal justice. This “Smart On Crime” approach seeks to reduce the number of people behind bars, while still protecting public safety, by focusing on evidence-based policies that have been proven to be effective at reducing crime and recidivism.

One of the key components of the smart on crime approach is a focus on rehabilitation and reentry. This means investing in education, job training, and mental health and substance abuse treatment programs to help people who’ve been incarcerated successfully reintegrate into society and avoid reoffending. By investing in these programs, we can reduce the number of people who end up back in prison, while also improving public safety.2

Recidivism is the tendency of a convicted criminal to repeat or reoffend a crime after already receiving punishment or serving their sentence. The term is often used in conjunction with substance abuse as a synonym for “relapse” but is specifically used for criminal behavior. The United States has some of the highest recidivism rates in the world. According to the National Institute of Justice, almost 44% of criminals released, returned before the first year out of prison. In 2005, about 68% of 405,000 released prisoners were arrested for a new crime within three years, and 77% were arrested within five years.

Factors contributing to recidivism include a person’s social environment and community, their circumstances before incarceration, events during their incarceration, and one of the main reasons, difficulty adjusting back into normal life. Many of these individuals have trouble reconnecting with family and finding a job to support themselves. Incarceration rates in the U.S. began increasing dramatically in the 1990s. The U.S. has the highest prison population of any country, comprising 25% of the world’s prisoners. Prisons are overcrowded, and inmates are forced to live in inhumane conditions, even those who are innocent and awaiting trial.

The United States justice system places its efforts on getting criminals off the streets by locking them up but fails to fix the issue of preventing these people from reoffending afterward. This is why many believe that the U.S. prison system is greatly flawed. Recidivism affects everyone: the offender, their family, the victim of the crime, law enforcement, and the community overall. Crime can affect anyone in any community. If a previously incarcerated person is released only to repeat an offense or act out a new crime, there will be new victims. Furthermore, taxpayers are impacted by the economic cost of crime and incarceration as the average per-inmate cost of incarceration in the U.S. is $31,286 per year.

Steps can be taken during incarceration to decrease recidivism. First is assessing the risks for reoffending and the criminogenic needs that contributed to breaking the law, such as a lack of self-control or antisocial peer group. The second is to assess their individual motivators, followed by choosing the appropriate treatment program. The fourth step is to implement evidence-based programming that emphasizes cognitive-behavioral strategies, coupled with positive reinforcement that can help them recognize and feel good about positive behavior. Lastly, the formerly incarcerated need ongoing support from a good peer group, as repeat offenders who were in gang culture have the greatest challenge to stay away from that behavior.3

The Second Chance Act, officially known as H.R. 1593, was enacted on April 9, 2008. Its aim was to improve the reintegration of formerly incarcerated individuals into society. The Act provided federal grants to state and local governments and nonprofit organizations to support reentry programs.

Goals of the Act

Reduce Recidivism: The Act focuses on lowering the rates of reoffending among released individuals.

Enhance Public Safety: By supporting successful reintegration, the Act aims to improve community safety.

Support Services: It provides funding for various services, including:

- Employment assistance

- Substance abuse treatment

- Housing support

- Family programming

- Mentoring services

Nationally

Since its passage in 2008, the Second Chance Act has invested $1.2 billion, infusing state and local efforts to improve outcomes for people leaving prison and jail with unprecedented resources and energy. Over the past 15 years, the Bureau of Justice Assistance and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention have awarded funding to 1,123 Second Chance Act grantees to improve reentry outcomes for individuals, families, and communities.1 And critically, the Second Chance Act-funded National Reentry Resource Center has built up a connective tissue across local, state, Tribal, and federal reentry initiatives, convening the many disparate actors who contribute to reentry success.

The result? A reentry landscape that would have been unrecognizable before the Second Chance Act’s passage. State and local correctional agencies across the country now enthusiastically agree that ensuring reentry success is core to their missions. And they are not alone: state agencies that work on everything from housing and mental health to education and transportation now agree that they too have a role to play in determining outcomes for people leaving prison or jail.

Community-based organizations, many led or staffed by people who were once justice involved themselves, are contributing passion and creativity, standing up innovative programs to connect people with housing, jobs, education, treatment, and more. Researchers have built a rich body of evidence about what works to reduce criminal justice involvement and improve reentry outcomes, allowing the National Reentry Resource Center to create and disseminate toolkits and frameworks to support jurisdictions to scale up effective approaches. And private corporations that once saw criminal justice involvement as fatal to a candidate’s job application are now using their platforms to champion second chance employment as both a moral and business imperative.

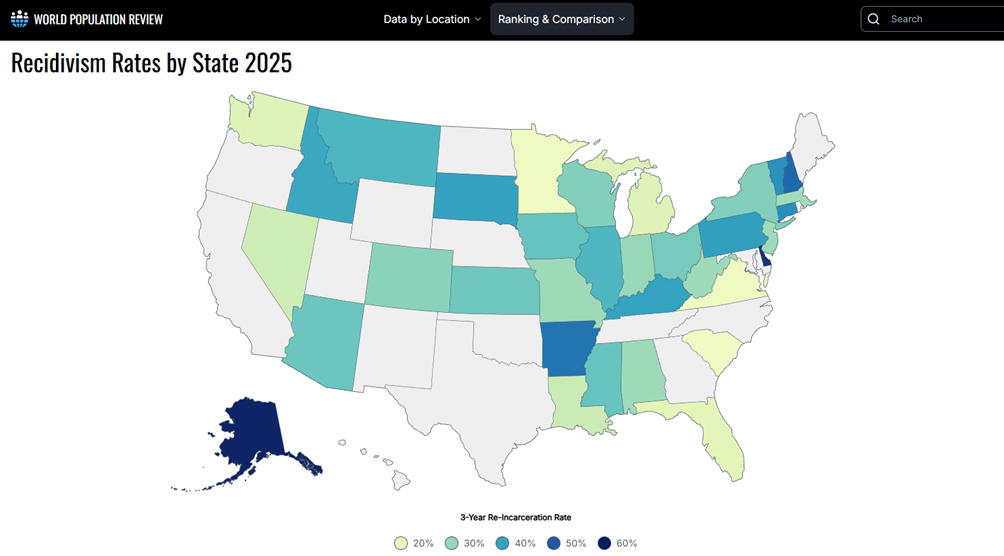

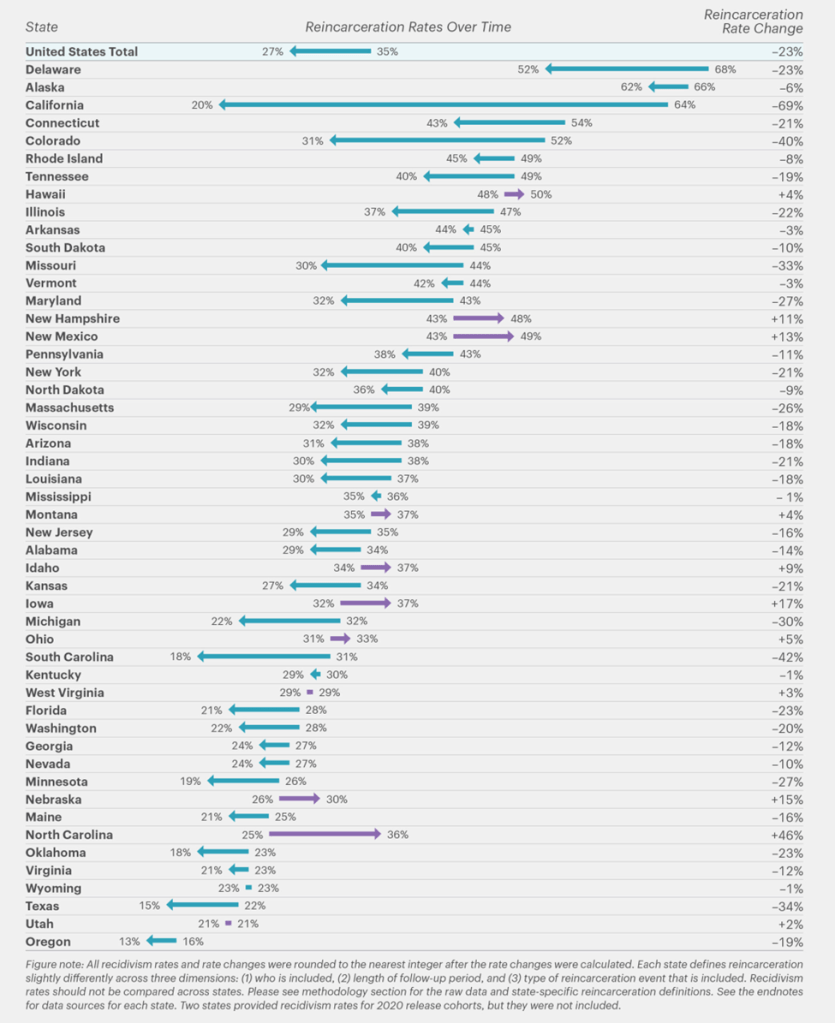

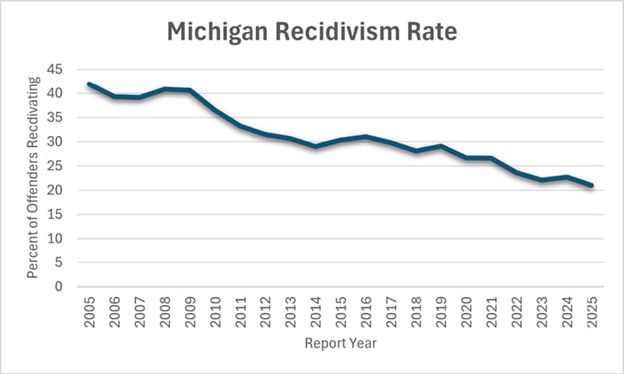

The efforts of these key stakeholders are bigger, bolder, and better coordinated than ever, and they are producing results. Recidivism has declined significantly in states across the country, saving governments money, keeping neighborhoods safer, and allowing people to leave their justice involvement behind in favor of rich and meaningful lives in their communities.4

Closer to home

Michigan currently has a recidivism rate measured at 21.0%, the lowest rate on state record. The rate measures those who are three years from their parole date and records how many individuals have reoffended and returned to prison within that timeframe. The latest report shows a 79.0% success rate of those paroled not returning to prison.

MDOC has undertaken numerous evidence-based programs to continue reducing the state’s recidivism rate including supporting access to vital documents, housing, and recovery resources; job placement assistance; and effective supervision and care while individuals are incarcerated and on parole.

Prison educational programs have been seeing significant success with thousands of graduates since their inception. There are now 14 skilled trades programs and 12 post-secondary education programs operating in correctional facilities across the state, with additional programs expected to be added next year.

“This report shows that when we provide a full circle support system to those reentering our communities, they are less likely to return,” Director Heidi E. Washington said. “I am proud of our dedicated MDOC staff, and appreciate the support of our partners, all of whom help motivate and lift up those we are welcoming back into our communities. With increased support for reentry programing, we are very likely to see the state recidivism rate continue to decline.”

This report connects directly with a recently released MDOC prison population report which showed the lowest prison population since 1991, with 32,778 incarcerated individuals statewide, down from a peak of 51,554 individuals in 2007, illustrating success in rehabilitating offenders.5

Why this matters today

The Second Chance Act is up for reauthorization again this year. It has not attracted much public attention with all the other actions taking place in Washington that have overshadowed this crucial piece of legislation. The Second Chance Reauthorization Act of 2025 (H.R. 3552/S. 1843) aims to enhance rehabilitation efforts for individuals transitioning from incarceration back into their communities.

Key Provisions

Grant Programs

- Reauthorization: Extends grant programs for five additional years.

- Support Services: Provides funding for reentry services, including housing, employment training, and addiction treatment.

Focus Areas

- Substance Use Treatment: Enhances services for individuals with substance use disorders, including peer recovery and case management.

- Transitional Housing: Expands allowable uses for supportive housing services for those reentering society.

Impact and Importance

- Recidivism Reduction: Research indicates that effective reentry programs can reduce recidivism rates by 23% since 2008.

- Community Safety: By supporting successful reintegration, the Act aims to improve public safety and reduce the burden on the criminal justice system.

The Senate passed the Act on October 9, 2025, as part of the National Defense Authorization Act, and it is now awaiting consideration in the House of Representatives. Tell your Representatives to pass this bill and see it enacted in law so that the progress made in reducing recidivism and US prison populations will continue.

Find Your Representative | house.gov

End Notes

1 https://www.splcenter.org/resources/guides/trump-tough-on-crime-memo-faq/

2 Why the Tough on Crime Approach is Failing and What We Can Do About It – LAMA

3 Recidivism Rates by State 2025